Protecting the Fathers and Families of Tomorrow

June 10, 2018 • community

School of Public Health & Texas Center for Health Disparities

Community Blog

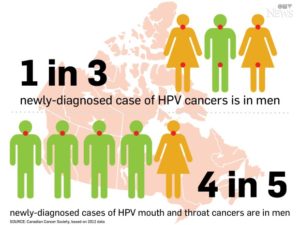

A study released in 2012 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology using NHANES data in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that 10.1 percent of men were infected with HPV of one type or another, compared with just 3.6 percent of women. Spread orally or genitally through intimate sexual contact, the virus’s effect on both genders and their future families can be devastating.

The U.S. Health & Human Services Office of Women’s Health produces a website, womenshealth.gov where Michelle Whitlock, author of How I Lost My Uterus and Found My Voice, shares her story of a cervical cancer diagnosis at the age of 27. After describing her heartbreaking journey through diagnosis, treatment, harvesting her eggs for the chance at a family and recovery, she goes on to advocate for cervical cancer prevention. She emphatically states, “Not only do we have access to preventive screening tools, but we have vaccines that can prevent cancer! Today, there are vaccines that protect against HPV-related cancers and genital warts. I only wish they had been available when I was younger.”

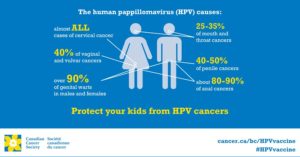

Consisting of over 150 types, the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is easily one of the most spread sexually transmitted infections today. HPV is so common, most women and men who are sexually active will be infected at some point in their lives. While this may be surprising, the most alarming fact is that HPV is a direct cause of several types of cancer, including cervical, penile, anal and head and neck cancers, as well as genital warts. In fact, HPV is responsible for 99% of cervical cancer!

In 2006, a vaccine was developed to protect children and young adults against the strongest cancer and wart-causing strains, with a near 100% effective protection rate. Children can be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine as young as age 9, and as old as 26. Unfortunately, nationwide vaccine rates for the HPV vaccine has been low, with only 42% of girls and 28% of boys completing the series of shots.

So, with such an effective vaccine available to the public, why haven’t we seen higher vaccination rates?

So, with such an effective vaccine available to the public, why haven’t we seen higher vaccination rates?

The answer to that question is complicated. Vaccines are a controversial subject. While several studies have been conducted over the years to eliminate fears about vaccines, there are still many who believe that vaccines have serious side effects based on misinformation. When talking to individuals who are worried about vaccine risks, it’s not enough to provide clear facts based on science. We need to discuss the importance of the HPV vaccine (and other vaccines) with an open mind and an understanding heart.

While HPV was initially thought to be an infection that harmed girls, research shows it can also harm boys. While girls experience cervical cancer, and vaginal/vulvar cancer, boys are susceptible to penile cancer. Both boys and girls can be affected by anal and head and neck cancers, with homosexual and bisexual men experiencing a higher rate of anal cancer. In addition, studies have suggested that boys can be reservoirs of HPV, passing it on to successive sexual partners. While we do not currently have an HPV screening test for boys, vaccinating them to prevent the spread of the virus as well as protecting them against cancer-causing strains is an important public health mission.

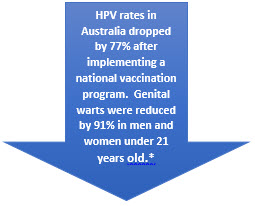

National policy could assist in eradicating HPV by mandating or subsidizing the vaccine. Since 2007, the Australian government has provided the HPV vaccination for free in schools for both girls and boys. Since the program began, the rate of HPV decreased to an all-time low, and Australia may be set to eradicate cervical cancer entirely from its population.

In the short term, we could all play a part in improving HPV vaccination rates by talking about the virus and the vaccine with our friends and neighbors. The simplest casual conversation could lead to the biggest social change.

Authors:

Shane Fernando PhD, Teresa Wagner, DrPH, MS, CPH, RD/LD, CHWI

Dr. Fernando is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at UNT Health Science Center with training in epidemiology. His community-based research is largely focused on the impact of health disparities in children and teens across various cultural, gender and socioeconomic indices in Fort Worth through the use of the UNTHSC Pediatric Mobile Clinic.

*www.hpvvaccine.org.au

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD006882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Social media