Reflections on equity, diversity and inclusion

March 4, 2019 • community

School of Public Health & Texas Center for Health Disparities Community Blog

Last Fall I was asked to chair an ad hoc (temporary) committee to develop a diversity and inclusion plan for our School of Public Health (SPH). This seemed like a fairly straightforward task for a couple of different reasons. First, our accrediting body, the Council on Education for Public Health, provides us with a clear set of questions and sound logic to proceed with our plan.

Second, issues of cultural competence and diversity are considered foundational in our public health base of knowledge and skills. Among the 22 competencies expected of our Master of Public Health degree graduates, 5 include explicit language related to equity, diversity or inclusion and most others cannot be successfully accomplished without incorporating these concepts.

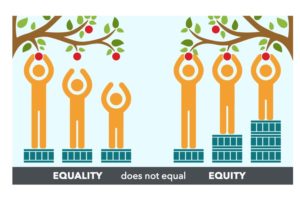

Furthermore, much of our focus in public health is on the extent to which conditions of where we live, learn, work, and play affect our health.  These conditions are referred to as the social determinants of health and form the basis of the US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People 2020 framework. As part of our teaching, research and service, we routinely discuss issues of health disparities and inequities. Our monthly blog often addresses disparities in the social determinants of health, such as highlighting racial inequities in prostate cancer mortality and youth drowning, or gender inequities in maternal mortality and intimate partner homicide.

These conditions are referred to as the social determinants of health and form the basis of the US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People 2020 framework. As part of our teaching, research and service, we routinely discuss issues of health disparities and inequities. Our monthly blog often addresses disparities in the social determinants of health, such as highlighting racial inequities in prostate cancer mortality and youth drowning, or gender inequities in maternal mortality and intimate partner homicide.

Humbled and Transformed

Despite the fact that my daily work evolves around promoting public health competencies and engaging diverse communities, I found the experience of chairing this ad hoc committee to be both humbling and transforming. It has set me on a journey of discovery and reflection, added another lens to view the world, deepened the piles of books in my home and office (as well as the virtual ones in my Audible library), and strengthened my resolve to continue this work.

Before I share the details of this transformation, I believe it is important to explain where I began. I am a white, heterosexual woman. I grew up in a middle-class family with two parents who hold graduate degrees and provided a nurturing environment with high expectations and healthy boundaries.

In other words, I have lived a very privileged life and I continue to benefit from these privileges. This is important, because whether we acknowledge it or not, the decisions we make, and our interactions with one another are shaped by our privileges and our socialization.

During my life journey, a number of experiences have sensitized me and helped me understand my privilege. These include having my dad come out as gay during my early adulthood; living as a statistical ethnic minority in Miami, Florida for seven years; marrying a man with a different race, ethnic, and socioeconomic background from me; giving birth to and parenting a mixed-race child; and experiencing years of microaggressions as a mixed-race family in Texas.

Too much information?

Why am I sharing these personal reflections? Because what I’ve learned is that doing this work in a meaningful way requires you to question all of your beliefs and decisions. As a school, we are in the process of examining our policies, procedures and practices through a lens of equity and inclusion. Because many of us identify ourselves as social scientists, we want to believe that we are doing so with objectivity. However, without personal reflection, the “objective” criteria that we are using may in fact be influenced by biases rooted in privilege, history, and socialization.

Our Committee

One of the best parts of chairing the ad hoc committee was working with the committee members, who each contributed valuable perspectives and engaged in thoughtful discussion. The committee included UNTHSC administrators, faculty, staff and student volunteers, as well as community members, and a UNT system administrator. These 12 people brought diverse perspectives, as well as experience in promoting equity, diversity and inclusion in higher education and community settings. This productive group worked intensively between November 2018 and February 2019 to develop and draft an initial plan.

Our process

In a little over three months, we accomplished the following expectations set by our accrediting body:

- Identify and define priority under-represented groups of faculty, staff, and/or students

- Establish goals to increase representation of the under-represented groups identified in #1.

- Identify the strategies used to advance and evaluate the goals established in #2.

- Describe the strategies planned to create and maintain a culturally competent environment.

We also developed a School statement on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, as well as a logic model framework to show how we will achieve our goals.

We began with a systematic review of information, which included:

- Demographic (race, gender, ethnicity) information about our faculty and students, as well as other Schools and Programs of Public Health

- Demographic information about Texas, the North Central Texas region, and our surrounding county

- Information about the operations of our school, including but not limited to: (1) curriculum design, (2) student recruitment practices, (3) faculty research areas, (4) faculty and staff search and hiring practices, (5) faculty, staff and student involvement in the community.

- Published reports and articles addressing issues of equity, diversity and inclusion in higher education and our surrounding community,

- Best practices and approaches to promoting equity, diversity and inclusion

- The mission, vision and values of our institution

During our review, we talked about the importance of preparing our students to practice in the surrounding community, engaging and serving the community with respect and competence, and addressing barriers to recruitment and retention of diversity faculty, staff and students. We discussed what we believe we’re doing well and reflected on areas we need to improve.

We spent hours developing the following statement on behalf of our school:

Our commitment to equity, diversity and inclusion

Our work, rooted in social justice, leads to solutions for a healthier community. We aspire to create an academic environment where an equitable, diverse and inclusive culture is part of our core values. We seek and embrace diversity of thought, people, culture, and experiences. These principles enhance our ability to prepare the public health workforce, generate knowledge, and make positive contributions to our community.

We determined that it is important for our faculty, staff and students to demographically align with our surrounding region and set a specific goal to: Establish a culture of equity, diversity and inclusion that supports the recruitment and retention of African-American and Hispanic students and faculty.

We selected a variety of strategies to achieve our goal and stated commitment, including:

- Changes to how we recruit, hire and retain faculty, staff and students

- Implementation of a life course pipeline development perspective to mentoring and engagement of faculty, staff, and students

- Establishing a standing committee on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion that allows us to evaluate, monitor, and make recommendations to improve the culture of our school

Our plans were shared at faculty and staff meeting and with additional feedback, we are moving forward with our long-term plans.

(Turner, 2018, p. 11)

A call to action

Last November, I went from feeling relatively well prepared to facilitate the process, to recognizing that this wasn’t just an ordinary committee. We were embarking on a careful and difficult journey to improve the culture of our school. We were tackling issues that are hard to talk about. We had to prioritize certain under-represented groups, which inherently involves choice and selection. We had to use the information about our faculty, staff and students that was available to us; which did not include religion, disability status, sexual orientation, or other characteristics that often form the basis for bias, discrimination and exclusion.

The magnitude of these challenges left me feeling humbled and under-prepared. As a result, I began reading books and other materials that have helped me better reflect on the lens I use in my work and daily life. A few major take-ways from this exploration are as follows:

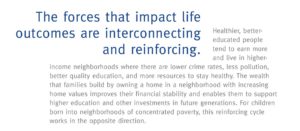

- It is important to distinguish between prejudicial beliefs, discriminatory actions, and racism (sexism, or any other -ism). We all have biased and prejudicial beliefs and sometimes we act on those beliefs with discriminatory behaviors. Racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, age-ism, able-body-ism and all other “-isms” are rooted in structural inequities based on power differentials. If we are in a position of power and privilege, we have to carefully dissect the assumptions we make about policies, procedures and practices. If a process consistently yields disparate outcomes, then it is upon us to not only examine reasons for the disparity, but to consider ways to correct the inequities.

- People of color who work in a primarily white institution face barriers and carry burdens that frequently go un-noticed. This has been referred to as “invisible labor” and “cultural taxation” (June, 2018) due to the time and energy they invest in un-recognized mentoring and being asked to provide their perspective on behalf of under-represented groups. A poignant concept addressed in the book “White Fragility” (DiAngelo & Dyson, 2018) was that we can’t expect under-represented groups to continuously educate us about their life circumstances. We must educate ourselves by reading books, watching films, and finding other materials to help us gain understanding and humility.

- A long-time sociology theory proposes that situations perceived as real are real in their consequences (Thomas & Thomas, 1928). I have found it helpful to consider this logic in the context of microaggressions and discrimination. Under-represented groups face forms of covert discrimination on a regular basis. If I make a decision that is not based on bias and prejudice, but could be potentially interpreted as such, I need to consider the potential harm that could be done. Leaving a person to wonder to if they were treated differently based on an under-represented status can be harmful, even if the harm was unintended. While this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t make decisions that might be mis-interpreted, it does mean that we should give careful consideration to all of the intended and unintended consequences of our actions.

- Structural inequalities are so pervasive, we don’t always perceive them as contributing to prejudice, discrimination and the variety of -isms. We are all products of our socialization, which means that we may be entirely unaware that some of our behaviors are harmful. As a white person, the question I must ask of myself is not whether or not I am racist, but what beliefs and behaviors do I hold that are rooted in structural inequalities based on race? Are there ways that I unintendedly perpetuate inequities and exclusion? What else can I do to prevent harm?

What are your take-aways? Next steps? What can YOU do to make your work environment more equitable, diverse, and inclusive?

Blog Author:

Emily Spence-Almaguer, PhD, MSW, Associate Dean for Community Engagement and Health Equity, Associate Professor, School of Public Health

Director of the Community Engagement and Dissemination Core, Texas Center for Health Disparities

University of North Texas Health Science Center

I wish to offer great appreciation to members of the SPH Ad Hoc Committee on diversity and inclusion and others who supported these efforts:

Sushmitha Ananth, MPH student, SPH

Carolyn Bradley-Guidry, Associate Professor, Director of Diversity and Inclusion, Dept of Physician Assistant Studies, UT Southwestern Medical Center; DrPH student, SPH

Wanda Boyd, Director of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, UNT System

Jose Gonzalez, Vice-President, Center for Children’s Health (retired), Cook Children’s Health Care System

Beth Hargrove, Director of Admissions, SPH

Simeon Henderson, District Executive Director, McDonald Southeast YMCA of Metropolitan Fort Worth, Director, Center for Diversity and International Programs (CDIP)

Associate Professor, Microbiology, Immunology and Genetics, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences

Melissa Lewis, Professor, Department of Health Behavior and Health Systems, SPH

Sumihiro Suzuki, Chair, Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Associate Professor, SPH

Erika Thompson, Assistant Professor, Department of Health Behavior and Health Systems, SPH

Teresa Wagner, Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health Education, SPH

*Special thanks to Shlesma Chhetri, Terry Voss and Nellie Berunem for their support and assistance

References:

Association of American Medical Colleges (2016) Diversity and Inclusion in Academic Medicine: A strategic planning guide, 2nd edition. ISBN: 978-1-57754-154-7, www.aamc.org

Chronicle of Higher Education (2018). Idea Lab: Colleges Solving Problems: Faculty Diversity. Washington DC: https://store.chronicle.com/collections/idea-lab-colleges-solving-problems/products/idea-lab-faculty-diversity

DiAngelo, R. & Dyson, M.E. (2018) White Fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

June, A.W. (2018) Labor of Minority Professors, In: Idea Lab: Faculty Diversity, Chronicle of Higher Education, pp. 26-30.

Turner, A. (2018). The business case for racial equity: A strategy for growth. W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Retrieved from: https://www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2018/07/business-case-for-racial-equity

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD006882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Social media