High price of survival

By Jan Jarvis

Nearly three decades ago, HIV threatened John’s life.

But instead of killing him, the virus inspired him to live a more successful and ultimately rewarding life. An unruly college student in the 1980s, John traded late-night parties for early bedtimes. He began eating healthy meals, exercising regularly and taking antiretroviral drugs.

At a glanceThe positiveHIV-positive patients are living longer. In fact, patients 50 and older make up the fastest-growing segment of the HIV population. The negativeThe health implications of living with HIV are great. Rates of heart attacks, cancer and kidney disease are higher. So is depression. Many older HIV patients suffer memory deficits. Seeking answersUNTHSC researchers are studying the effects of HIV to understand how the virus infects cells and how treatments can be improved |

“I knew that if I wanted to live, I had to be more disciplined,” said John, now 50, who did not want to be identified because of the stigma associated with HIV. “I needed money and I needed health insurance if I was going to survive.

“At the end of the day, I feel like I was pretty lucky. I think about HIV every day, but I don’t think about dying.”

He never imagined the price he would pay for survival: two hip replacements, two shoulder surgeries, cancer and a mini-stroke. The drugs are saving his life, but at a tremendous cost to his health.

That’s the catch-22 for those 50 and older, a group that makes up the fastest-growing segment of the HIV population. Today, 40 percent of HIV-positive adults in the United States are 50-plus, a statistic that is expected to exceed 70 percent within four years.

Heart attacks, cancer and late-stage kidney disease are substantially more likely to occur for this group. Up to 60 percent have memory deficits. Many are infected with Hepatitis B and C. Depression strikes at five times the rate it does their peers.

“People have the perception that HIV is like having diabetes,” said Kathleen Borgmann, Laboratory Manager, Institute for Molecular Medicine. “But it’s more like having cancer and going through chemo every day of your life.”

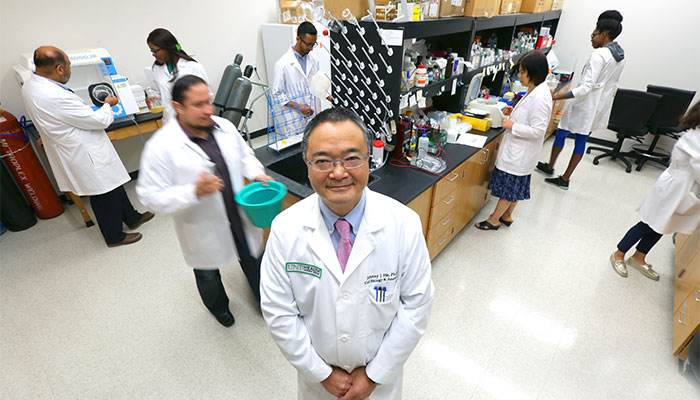

Researchers at UNT Health Science Center are studying the effects of HIV with the goal of understanding how the virus infects cells and how the disease could better be treated. Their research paints a startling portrait of the new face of HIV.

“Yes, people are living longer with HIV, but their aging is accelerated by at least 10 years,” said Johnny He, Associate Dean, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and Professor, Institute for Molecular Medicine. “So not only do they look like they are 50 at 40, they feel it.”

New therapies are working, but there’s a problem, said Anuja Ghorpade, PhD, Interim Vice President of Research and Innovation.

“We have been successful at keeping patients with HIV alive,” she said. “But we don’t have a way to cure them.

Aging with HIV

Frightened by the toxic effects of AZT, the first drug used to delay the effects of AIDS, John skipped treatment. But by 1993, his viral load was high and his T-cell count was almost non-existent.

“My immune system was wiped out,” he said.

Then in 1995 protease inhibitors were introduced, followed by highly active antiretroviral therapy. The combination turned HIV from a fatal disease into a chronic one for many, including John. The drugs were less toxic and resistance was slower to develop, which made it possible for him to have a successful career, enjoy a long-term relationship and raise a family.

But the 2000s brought new health challenges. Avascular necrosis, a condition that causes bone tissue to die, led to two hip replacements and two shoulder surgeries. His blood pressure and cholesterol shot up, most likely due to the protease inhibitors. He had 10 operations in all.

Although antiretroviral therapy can prevent HIV from replicating, it never completely destroys the virus, said Patrick Clay, PharmD, Professor of Pharmacotherapy. This may contribute to stress and inflammation, which over time weakens the immune system and makes the body vulnerable to other comorbidities.

“HIV is by definition a chronic virus,” Dr. Clay said. “It keeps the body’s immune system revved up. This perpetual stress is what causes an earlier onset of diseases we typically wouldn’t see until later in life.”

Damage to the brain

HIV gets into the brain early and stays there, causing damage over decades.

“When you look at the brain of a 40-year-old with HIV, it looks like the brain of a 50- or 60- year-old without HIV,” Borgmann said.

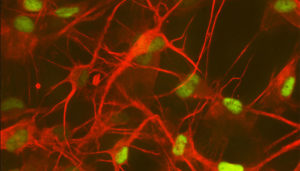

The question is why. The answer may be found in astrocytes, star-shaped cells in the brain that are supposed to protect nerve cells.

“Astrocytes are to nerve cells what I am as a mother to my children,” Dr. Ghorpade said. “If there’s an injury, they rush to the site.”

Children eventually outgrow this need, but astrocytes never do. For up to 70 percent of patients with HIV, this can result in a decline of neurological function.

“Some people don’t have any noticeable changes over the years or it’s not enough to interfere with their daily lives,” Dr. Ghorpade said. “But others show significant cognitive decline at an early age.”

Drugs used to treat HIV have very limited access to the brain and are mostly toxic to brain cells.

“The drugs help people live longer, but the state of their brains is not as functional,” Dr. He said. “The brain is a very privileged organ that is very selective about what it lets in. As a result, the virus is able to hide in the brain and replicate.”

The risks are even greater for crystal meth users, who are 20 percent more likely to contract HIV, said Dr. Ghorpade, who is studying the effects of meth and HIV on the brain as part of a $1.8 million study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“We know that using meth increases the potential of getting the HIV infection,” she said. “But is that because meth users are more like to engage in risky sexual behaviors or does meth somehow activate the virus?”

UNTHSC researchers also are looking at biomarkers in the blood that could be used to predict which HIV-positive patients will likely develop dementia. The research could be applicable to other neurocognitive diseases as well.

“Ultimately, we think that the way astrocytes misbehave during HIV is similar to the way they misbehave with Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis,” said Sangeeta Shenoy, Clinical Research Administrative Coordinator.

Helping and hurting

Every night, John takes two pills that keep his viral load at undetectable levels.

It’s a far cry from the 1990s when people were taking upwards of 30 pills a day. Today, someone with HIV can take three drugs, in a single pill, once a day, Dr. Clay said.

But because the body breaks down drugs differently in people with HIV, medication management becomes more challenging. A 5-milligram dose of a cholesterol-lowering drug, for example, acts like a 20-mg dose in an HIV-positive individual, Dr. Clay said.

The side effects can be daunting. But for now, they are unavoidable.

“The time from infection with HIV to death is about seven years without medication,” Dr. Clay said. “My advice for anyone with HIV is to start medication as soon as you are diagnosed and never stop.”

At 50, John believes he has not aged as fast as others with HIV and credits his lifestyle, which includes mental exercises and social interaction, with keeping him healthy. Even if the drugs he takes now stop working, he believes new discoveries are right around the corner that will allow him to live a live a long life.

“I feel real positive about things,” he said. “It’s been over 25 years, and hey, I’m still here.”

![Uyen Sa Nguyen Scaled[58]](https://www.unthsc.edu/newsroom/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/Uyen-Sa-Nguyen-scaled58-145x175.jpg)

Social media