Pest control

By Jeff Carlton and Jan Jarvis

At a glanceThe threatMosquitos, ticks and other biting arthropods can transmit serious diseases to humans, ranging from West Nile virus to Lyme disease. The responseUNTHSC researchers are seeking better preventative agents and more effective monitoring systems to counter these nasty disease-carriers. The bottom lineBecause there’s no cure for many of these diseases, avoiding risk is key. “There’s no better treatment than prevention,” Dr. John Schetz said. |

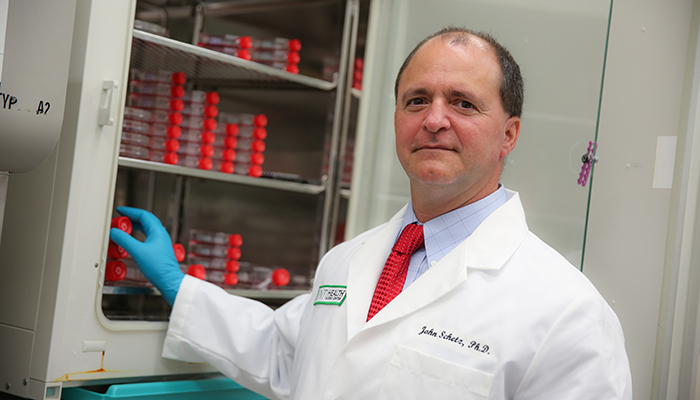

A simple bite from the lowly mosquito, says scientist John Schetz, can lead to a Zika virus infection causing devastating birth defects such as microcephaly.

Or it can put a person at risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune and neurological disorder that can result in temporary paralysis, including of the diaphragm, rendering an individual unable to breathe without mechanical ventilation.

Another possibility: contracting chikungunya or dengue fever. The former causes severe fever and debilitating joint pain, the latter once was colloquially referred to as “bone-break fever” because of the pain it inflicts on those unfortunate enough to contract it.

While there is no cure for many of the diseases carried by mosquitos, there is one surefire way to reduce the risks.

“There’s no better treatment than prevention,” said Schetz, PhD, Professor of Pharmacology and Neuroscience in the Center for Neuroscience Discovery. “With the exception of Zika, which apparently can also be sexually transmitted, disease prevention is nearly guaranteed if mosquito bites can be avoided.”

His UNT Health Science Center allies in this fight against insects, arachnids and the diseases they carry include a medical entomologist who tracks West Nile virus transmission rates across Fort Worth and helps city officials decide whether to spray for mosquitos, and a microbiologist who uses advanced genetic techniques to test ticks submitted from around Texas for diseases such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Lyme disease.

Together, these scientists are pushing the boundaries of discovery for better preventive agents or more effective monitoring systems against some of the nastiest diseases carried by mosquitos, ticks, and other biting arthropods.

Testing ticks from across Texas

When it gets hot and muggy, ticks by the hundreds show up at the Health Science Center.

Fortunately, they’re all dead.

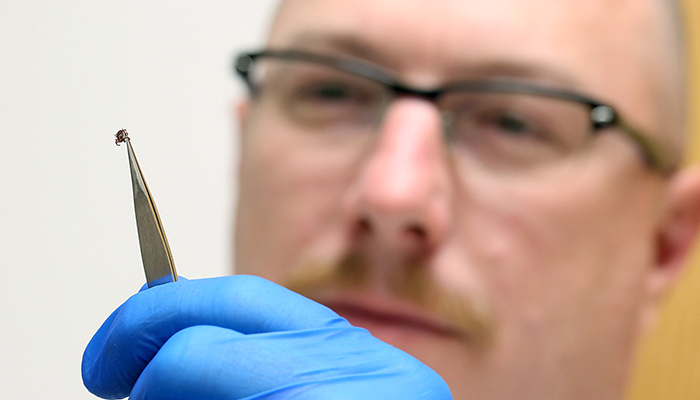

At the Tick-Borne Disease Research Laboratory, the small arachnids are analyzed and tested with the same DNA methodologies used in UNTHSC’s cutting-edge forensic genetics labs, said Michael Allen, PhD, Lab Director.

“Sometimes they are all mashed up to the point where they are unrecognizable,” said Dr. Allen, Associate Professor of Molecular and Medical Genetics. “But even then we can still identify the tick’s DNA.”

Year round, but especially during the summer, hundreds of ticks taken off humans are delivered to UNTHSC for analysis of disease-causing organisms such as Borrelia and Rickettsia. While most ticks are merely annoyances, some can cause serious diseases.

“There are a lot of different species of ticks, and each species carries different diseases,” Dr. Allen said. “We test for four common nasty bacteria.”

Deer ticks are known to transmit the bacteria that cause Lyme disease, a serious condition that affects about 300,000 Americans each year. Rocky Mountain spotted fever, caused by certain species of Rickettsia bacteria, can result in acute illness with a rash and high fever.

“If you get this from a tick, there’s a good chance it will kill you if it isn’t treated,” Dr. Allen said. “Left untreated, it has about a 30 percent mortality rate. Fortunately the disease responds well to common antibiotics when properly diagnosed.”

Any Texas resident can submit tick samples to the Texas Department of State Health Services, which then sends them to UNTHSC for free testing. Only specimens from a Texas address are covered under an agreement with the state. This also includes ticks picked up by Texans traveling elsewhere.

Tick samples also can be submitted directly to Dr. Allen’s lab and will be tested for a fee. Out-of-state residents and people interested in having ticks tested from their pets can submit samples – also for a fee.

During the summer when children go away to camp and people spend more time outdoors, it’s not uncommon to discover the tiny creatures crawling, or worse, sucking on their skin. That is when disease transmission poses the greater risk. A tick can feed for a week and be full for a year.

Once a tick attaches to the skin and starts sucking blood, the best defense is to quickly remove it and send the sample to the state.

“If a tick is found crawling on the skin it’s not a problem,” Dr. Allen said. “But the longer it stays on the skin the more likely it will bite and start feeding.”

Watching for West Nile virus

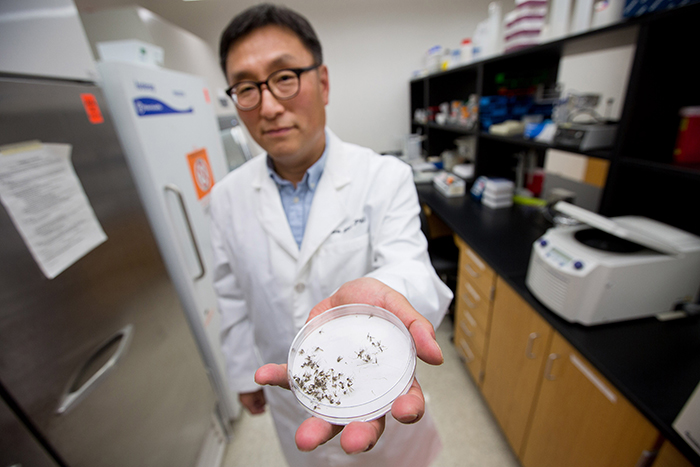

Every year starting in late May, graduate students from the School of Public Health fan out across the city twice a week to more than 60 local traps set up in residential areas, parks and outside fire stations.

Their mission: to collect and analyze mosquitos for any signs of West Nile virus, part of an innovative partnership between the Health Science Center and the City of Fort Worth.

Using grass clippings and standing water as bait, Joon Lee, PhD, and his team of graduate students set traps each Monday and collect mosquitos every Tuesday, allowing Dr. Lee to conduct testing in his lab and data analysis on Wednesdays and Thursdays. On Fridays, he provides a report and recommendations to Fort Worth officials.

Based on test results, UNTHSC public health experts make weekly recommendations to city officials about whether any intervention methods or precautionary measures should be considered.

Dr. Lee, Associate Professor of Environmental and Occupational Health, previously coordinated the mosquito-carrying virus tracking program for Iowa, Alabama and the Tennessee Valley Authority. When West Nile virus first became a public health threat, he trained county health departments on insect control and virus surveillance in one of the highest risk areas for the New York State Health Department.

“We’re applying science-based best public health practices to create a West Nile virus-prevention and control program that can be used as a model for other cities in Texas,” Dr. Lee said.

A better mosquito repellant

The tricky part about preventing mosquito bites, says Dr. Schetz, is that no one is exactly sure how the leading deterrent works.

The chemical compound DEET, found in the most popular and effective bug sprays, appears to affect the smell receptors on mosquitos, preventing them from noticing potential targets. A person who uses bug spray with DEET may, in effect, become invisible to mosquitos. Another theory is that mosquitos find DEET distasteful.

“But mosquitos are showing more tolerance to DEET,” Dr. Schetz said. “They may not bite you right away, but they become tolerant and could come back two hours later and bite you anyway.”

The mechanistically novel compounds that Dr. Schetz and his team are researching cause an effect unique to invertebrates. He said the research shows promise.

“Given the health risks posed by mosquitos, we’re in need of innovative solutions,” Dr. Schetz said. “We’re applying modern technologies to address these rapidly emerging threats.”

![Uyen Sa Nguyen Scaled[58]](https://www.unthsc.edu/newsroom/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/Uyen-Sa-Nguyen-scaled58-145x175.jpg)

Social media