Scientific Visionaries

From macular degeneration to glaucoma, UNTHSC researchers embark on new approaches to common eye diseases

Words: Jan Jarvis

Photos: Jill Johnson

Design: Carl Bluemel

Code: Mike Brown

In macular degeneration (AMD), the macula is disrupted by deposits called drusen (seen here as yellow clusters), or other age-related changes.

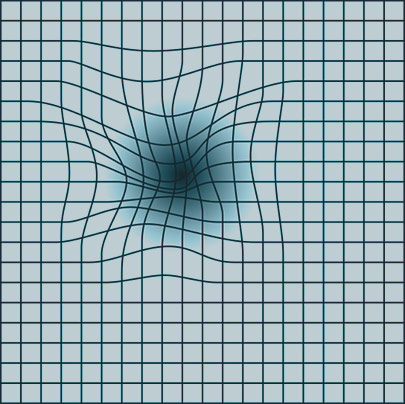

In macular degeneration (AMD), the macula is disrupted by deposits called drusen (seen here as yellow clusters), or other age-related changes. Someone with macular degeneration may see some of the lines of an Amsler grid as wavy or blurred, with some dark areas at the center.

Someone with macular degeneration may see some of the lines of an Amsler grid as wavy or blurred, with some dark areas at the center.The vision loss was hardly noticeable at first. But gradually, Roy Ryan’s world grew darker. “Now I can’t drive a car or play golf,” he said. “Most of the time my wife reads to me.”

For 14 years, age-related macular degeneration slowly robbed the Keller, Texas, great-grandfather of his sight. At 83, he relies on medication injected into his eyes every six weeks to stave off the disease’s progression.

But Ryan knows what’s likely ahead. There is no cure for macular degeneration, the leading cause of irreversible vision loss.

Still, he remains optimistic that in the years to come, new therapies will be developed that preserve or restore eyesight lost to the disease. Some of those therapies could come from the laboratories at UNT Health Science Center.

More than a dozen UNTHSC scientists are dedicated to unraveling the mysteries of the eye, a complex and confounding organ that processes light, interprets shapes and allows humans to see the world. At the North Texas Eye Research Institute (NTERI), founded in 1992, scientists strive for research outcomes that will lead to the development of new and effective treatments for ocular diseases such as glaucoma, macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, optic neuritis, and dry-eye disease.

Understanding how this window to the brain works and what goes wrong has been the life’s work of these researchers, who together bring decades of expertise from academia and industry to their labs. Discoveries made in those labs could one day change the way eye diseases and other conditions are treated.

Sai Chavala, MD, examines Roy Ryan, who suffers from age-related macular degeneration.

‘It can happen overnight’

Age-related macular degeneration sneaked up on Ryan, much the way it does for some 11 million Americans.

He had never heard of it until 2002, when his eye doctor diagnosed the dry form of macular degeneration. About 80 percent of cases fall into this category, which can go on for years without vision loss from retinal cell death.

But in 20 percent of those cases, the disease progresses to the wet form, which can lead to sudden vision loss, said Sai Chavala, MD, Professor of Surgery and Director of Translational Research for NTERI.

I’ve had patients go to sleep seeing well, and wake up the next day with a large dark spot in their central vision.

– Sai Chavala, MD

“It can happen overnight,” he said. “I’ve had patients go to sleep seeing well, and wake up the next day with a large dark spot in their central vision.”

Monthly injections into Ryan’s eyes have helped, but he lives each day knowing he could lose his sight at any time. To prevent such damage, UNTHSC is taking a different approach.

Dr. Chavala’s group has identified a novel method to generate retinal replacement cells without using embryonic stem cells.

“My dream is to one day grow a patient’s stem cells in a petri dish and convert them into retinal cells using a special ‘cocktail,’” he said. “I would then perform surgery to transplant these cells into the retina to rehabilitate vision.”

This therapy would be tailored to each patient. Since the cells are a genetic match, the risk of rejection is theoretically reduced, said Dr. Chavala, who is also an ophthalmologist with Retina Center of Texas.

Ryan and his family have financially contributed to Dr. Chavala’s research in an effort to help move this discovery from bench to bedside.

“We’re working on therapies right now that I hope will be available in the next decade,” Dr. Chavala said.

Dr. Chavala and ophthalmic technician Jennifer Herrera study a patient’s records.

Innovative approach

For years Laura Carter has worked as a production coordinator for UNTHSC, staring at a computer screen for hours, without so much as a hint of vision problems. But during a routine visit to her eye doctor, she learned the pressure in her eye was elevated.

Carter was diagnosed with glaucoma, the second-leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. An estimated 3 million Americans have the disease, but only half know it. African-Americans and Hispanics are at a higher risk for developing it.

Eye facts

In the time it takes to read a sentence, the eye completes 100 billion operations.

The average adult human eye has a diameter of 24 millimeters and weighs about 7.5 grams.

The eye is composed of 6 grams of water and 1.5 grams of cell tissue.

The human eye can distinguish 10 million colors.

Each eye has six muscles that control movement.

Having two eyes allows the brain to determine the depth and distance of an object.

Glaucoma is a slow-progressing, painless disease that over time causes someone’s visual field to get smaller and smaller, said Weiming Mao, PhD, Assistant Professor in NTERI. The center of one’s vision remains intact up until the person becomes blind.

While there is no cure, the disease is treatable with medications that indirectly reduce elevated pressure. But that’s not the underlying cause, and therapy eventually fails.

A signaling pathway that damages the front of the eye may provide an explanation. Growing evidence that glaucoma is a degenerative nerve disorder rather than just an eye disease could lead to treatments that not only spare vision but save lives, said Abe Clark, PhD, Professor and Executive Director of NTERI.

“We’re convinced this pathway is a major player in glaucoma and could lead to ways to inhibit or reverse the disease process so an individual ends up with a much healthier eye,” Dr. Clark said.

Glaucoma also damages the retina, optic nerve and vision centers in the brain.

“To really treat glaucoma, you have to protect all the areas that are damaged,” Dr. Clark said.

Researchers are closing in on several theories surrounding what goes wrong. Although the research is still in the early stages, growing evidence suggests that glaucoma might be an early warning for dementia, Dr. Clark said.

UNTHSC researchers from different disciplines are collaborating to find answers. Biomarkers that have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease are being studied by researchers in the Center for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Disease Research. Those same biomarkers have been linked to glaucoma and could lead to confirmation that eye disease is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s, Dr. Clark said.

“If glaucoma turns out to be an early warning sign, then that means we may be able to delay the onset of dementia using the same drugs we use for this eye disease,” he said.

Eye screenings are offered free to participants in the Health & Aging Brain Among Latino Elders (HABLE) study.

Improving vision health

Able Clark, PhD, Executive Director of NTERIWhen Fort Worth optometrist Jennifer Deakins looks into the eyes of an older patient, she’s searching for more than vision changes.

“We can see indicators of brain disease,” she said. “You can look right into the pupil and see it.”

On Fridays, Dr. Deakins and Dr. Clark screen for vision changes through the Health & Aging Brain Among Latino Elders (HABLE) study, a program that examines aging trends among Mexican-American men and women ages 50 and older.

For most participants, it’s a chance to get their vision screened at no cost. But for some, the test could lead to diagnoses they never saw coming: diabetes, hypertension, Alzheimer’s. The underserved Hispanic population is at especially high risk for glaucoma, diabetes, heart disease and other conditions that can be identified through the eye screenings.

“I’ve seen people who didn’t know that they had diabetes,” Dr. Deakins said. “But I can tell they most likely do based on what I see in their retina. Sometimes when I look at their eyes I see little hemorrhages and fluid leaks. Their vision can be 20/20, so they don’t realize they have a problem – but they do.”

NTERI is dedicated to bringing vision screenings to the community so the most vulnerable populations, from the youngest to the oldest, get the care they need to improve their lives, Dr. Clark said.

“Our team is committed to our institute’s mission and goals to improve the vision health of our community,” Dr. Clark said. “Our eye research and community outreach efforts are part of a bigger effort at the Health Science Center to push the boundaries of discovery and transform lives.”

“Our team is committed to our institute’s mission and goals to improve the vision health of our community.”

– Dr. Abe Clark

Social media